Much is made of individual statistics presented by Heroes of the Storm after a match. As someone who genuinely enjoys the analysis and interpretation of data, I’ve noticed some glaring oversights when it comes to how many players think the data represents the match and am taking this time to address them.

Blizzard has changed the match-end score screen several times over the past several years, and luckily the latest incarnation shows more data than ever about events that took place in a match. Note that I specifically don’t say “how a match went” or “how a player did,” because that’s ultimately not what these statistics show. No matter how granular the data set, there’s almost no way to recreate every aspect of the match.

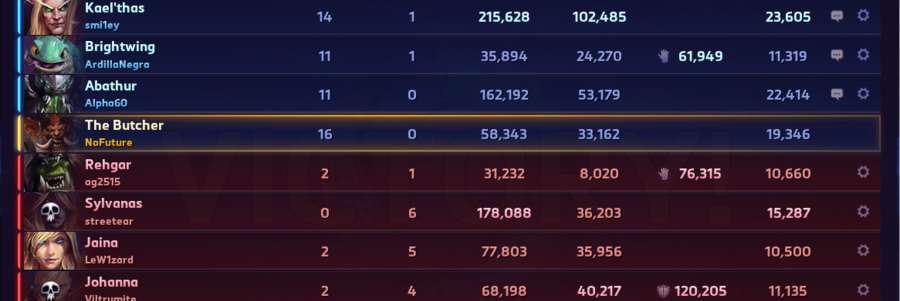

First, a primer on the statistics available to players:

- Takedowns – How many times a hero landed the killing blow on another

- Assists – How many time a hero was in the vicinity of an enemy hero death

- Deaths – How many times this hero died during the match

- Siege Damage – A cumulative total of all damage done to minions, mercenaries, and structures

- Hero Damage – A cumulative total of all damage done to enemy heroes

- Healing – A cumulative total of all health recovered and damage prevented through self-cast abilities (i.e. not through healing globes or by other heroes)

- Damage Taken – A cumulative total of all damage the hero received during the match

- XP Contribution – A cumulative total of all XP the hero contributed to the team total

All in all these look pretty straightforward; most games provide some measure of mid- or end-game statistic where players can see how well they’re doing, either relative to other players or against some real or imagined standard. With the variety of hero roles in HOTS, it isn’t always obvious whether high numbers mean a player is doing well, or if low numbers mean a player is performing poorly.

Several assassin-type heroes—most especially Genji, Orphea, and Valeera, among others—do not have methods to generate large amounts of area damage, and are instead laser-focused on getting the killing blow on individual heroes. Over the course of a match these characters may have very little Hero Damage on the boards, but will tend to rack up quite a number of Takedowns because they capitalize on the work put forth by their teammates; they are opportunists that prevent wounded foes from escaping battle.

More bruiser-like heroes such as Malthiel or Xul often don’t top the charts for kills, because they do a large amount of damage either over time or in a wide area. Their role isn’t necessarily to get the killing blow but to actively punish enemies that venture too far out, enabling the assassins to send them back to the Hall of Storms after the bruisers rough them up. Often players will conflate assassins and bruisers, and complain that their bruiser teammates don’t have “enough” kills when in reality they have a large amount of Assists, having performed a vital function to facilitate kills, and Hero Damage.

Some characters are very good at clearing out minion waves, either opening the way for direct-damage heroes to hit opponents or enabling friendly minions to advance. Characters like Murky, Gazlowe, and Azmodan often don’t contribute much to team fights in the middle of a lane, but do exceptionally well in other paths, acting as a force multiplier for allied NPCs. In my time playing Murky I often had the lowest number of Takedowns in the match (including the healers), but my Siege Damage was through the roof, because I focused on what the hero was good at—knocking down enemy minions, Often these characters aren’t expected to get many kills, but at the same time many players discount the effect they can have on a battle, or how their often invisible efforts make victory possible.

XP is an interesting one, in that ideally there shouldn’t be a wide spread within a given team. All heroes that are near an XP-granting event (minion death, fort destruction, mercenary camp conscription, et etera) share the XP for that event—if only one hero was nearby they would get credit for 100% of the total, where if three were each would get 33%. This can weight totals in favor of the off-lane or structure damage-based heroes, since they are often by themselves or otherwise engaged away from the rest of the team. Conversely, a hero that has a disproportionately low XP total likely wasn’t actively participating as much as other players—after all, characters that are dead or far away from team fights don’t contribute XP. I find it’s a good metric to determine total battle engagement.

Especially tanky characters such as Johanna and Garrosh often sit near the bottom of damage-dealing heroes, because their role isn’t to do damage or make kills—their role is to form the frontline defense for their team, keeping the softer heroes in the back from being easy prey for opportunistic enemies. Tanks often have a great deal of control over the battlefield, either by forcefully-maneuvering foes or making areas inaccessible. The performance of these characters is usually determined by the amount of Damage Taken, which also reflects very well on the team healer. Someone who is able to suffer terrible wounds and bounce back due to a quick-thinking support hero will be able to be a continued presence on the battlefield, hopefully taking more damage in the stead of their more squishy companions. A tank with a low Damage Taken score reflects either poorly on the player themselves (in that they weren’t out in front of the pack doing their job) or on their healer (meaning the tank could not afford to go back out after being damaged), and not automatically one or the other.

When it comes to interpreting data and comparing statistics, it’s very important to remember that the data only shows what the data shows—people make correlations and suggest trends. A favorite website to demonstrate this is Spurious Correlations, where you can clearly see that crude oil imports from Norway track very closely with the number of drivers killed in railway accidents. These two series of data have absolutely nothing to do with one another, but it’s easy to see how someone could draw (incorrect) conclusions about a relationship, just because someone made an argument for it.

HOTS is a complex game, where the entire team comes together for defeat or victory, and only in the most rare circumstances is a win or loss determined by a single player. Even those key moments which may tip the balance into one team’s favor or the other are predicated on an entire match of interactions and decisions. In short, the statistics don’t show the whole story, but can do a lot to suggest trends or patterns over time. Before you go yelling at a teammate for “poor” performance, remember that, in a vacuum, your own performance may look askance as well.