Magic: the Gathering may not have been the first collectible card game on the market, but for the past thirty years it has dominated game store shelves, influencing almost every other CCG developed or played since. Magic remains an iconic choice for players around the globe, with new sets being released all the time. Despite having over 22,500 unique cards, its core mechanics are not overly complicated, making it accessible to newcomers while remaining a complex hobby for season veterans.

This introductory guide covers the basic format and organization of the game, how it is played, and ultimately how a game is won, and is aimed at people who have never played Magic or those whose last brush with the game was years and years ago. I won’t go into deckbuilding strategy or deep mechanics, and consider it sufficient to say that almost everything I cover here is presented in a simplified way for the sake of instruction.

This post is a long one—nearly 5,000 words—but is designed to be as complete as possible to get new players up to speed while still being succinct. Please feel free to bookmark it and read it in chunks; the game can be complex enough without trying to force your way through a massive blog entry at the same time!

While it is possible to go overboard spending money for specific cards or ultra-synergistic decks, there are many starter decks and resources available that are very reasonably priced, and are generally a great deal for anyone interested in dipping their toes into the hobby. At the end of this post are some resources and suggestions, but first let’s talk about the game itself!

Worlds of Color

On the back of each Magic card there are five colored gems, representing give different colors of mana available to cast spells. When the game first started it was rare to have a deck containing more than one color, whereas now some decks have up to all five! While there is a great deal of in-game lore surrounding mana and the ways in which it can be wielded, in general each color has a theme to it, reflected in many cards of that color:

- Black: coming from swamps, black is the color of life drain. Demons, zombies, and horrors are heavily represented, as well as spells which damage the caster for increased benefit

- Green: the verdant forests and jungles are home to all number of creatures big and small, reflected in many creature-themed decks. Life gain is also a popular mechanic with green, as is enhancing creatures with enchantment spells

- Blue: only fools forget that, as the seas give life, so can they take it away. Blue decks are notorious for having cards which counter other spells, ensuring their effects never come to pass

- White: purity and solidarity reflected by endless rolling plains, white has historically been the color of protection, negating damage and protecting its cards against harmful effects

- Red: when mountains explode, they do so with unbridled violence. Powerful damaging spells, quick creatures, and mighty behemoths are all under its purview, with decks usually geared toward highly aggressive play

Every combination of two or three colors has a short-hand name among Magic players, representing in-lore forces which exemplified those ideals. These 20 combinations of two- and three-color mashups are too detailed for me to get into here, but most decks center around specific color effects, such as a red and blue deck casting big spells and countering anyone who tries to prevent the damage, or a black and white deck casting a lot of self-damaging spells with paired with life-gain to stay in the game.

The most basic element of Magic gameplay is the casting of spells—the playing cards—and nearly every spell requires mana to be played.

To cast a spell, a player has to have enough mana of the appropriate color(s) to do so. The layout of Magic cards is very standardized, and all cards with a casting cost have it printed in the upper-right corner. A card that has  as its casting cost requires a single black mana, while

as its casting cost requires a single black mana, while ![]() requires two: a blue and one of any color. Most often mana is generated by Lands, described below, but there are many other ways to generate it as well, namely through the use of some Artifacts or creature abilities.

requires two: a blue and one of any color. Most often mana is generated by Lands, described below, but there are many other ways to generate it as well, namely through the use of some Artifacts or creature abilities.

Game Setup

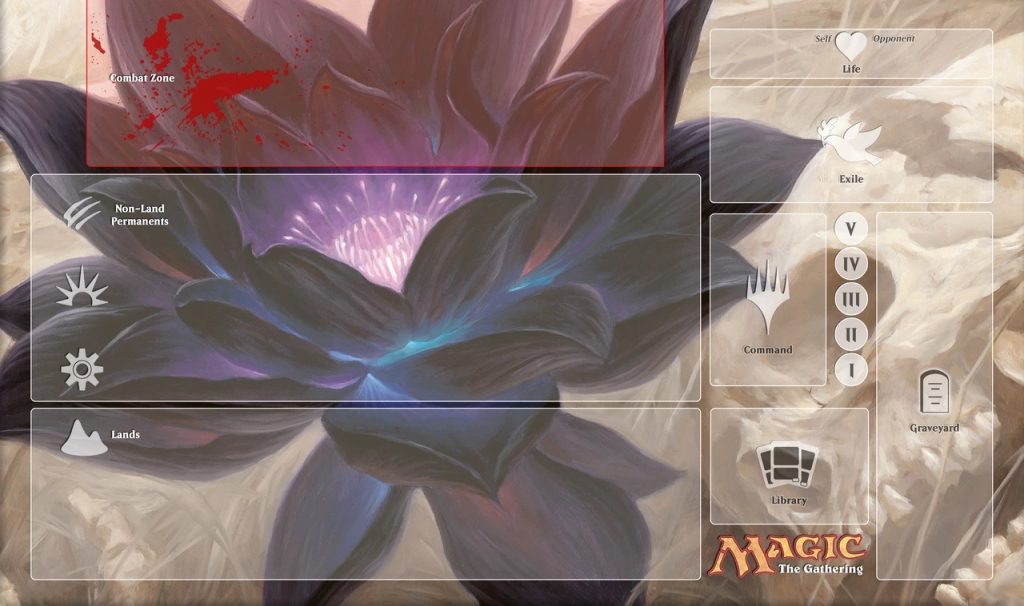

The playing field—usually a large physical or virtual table—is broken into different “zones” representing where cards can be at any given time. Cards move between these zones either in accordance to the base rules or when dictated by another card. For most Magic games, each individual player will have the following zones:

- Library: this is the player’s deck, from where cards are drawn over the course of the game. All cards are face-down so nobody knows what will be pulled next. The specific format of Magic being played will determine whether each deck is required to have 60, 100, or more cards in it, and what kind of cards can be included

- Hand: just as in poker or any number of other card games, each player has a “hand” or cards that are available to be played. Usually the contents of one’s hand are only known to that player, but there are spell effects which force the hand to be revealed to others

- Battlefield: the main play area, spells which create permanent effects—such as summoning creatures—are placed here after casting

- Graveyard: permanents that have left the battlefield, spells that were cast, and other cards that are essentially out of play go here. Some cards allow players to pull from or even play cards in the Graveyard

- Exile: something of a “super-graveyard,” when a card is exiled it is well and truly removed from the game; there are only a select few ways to interact with cards in exile. Often cards in exile are placed next to the Graveyard, turned sideways to denote their status

- The Stack: spells that are in the process of being played go here, a temporary holding place before they successfully resolve or are countered. Understanding how card interactions work on the stack is a key component to becoming a better Magic player, and this topic is explored in more depth later in this article

Types of Cards

In Magic, almost every card represents a spell you as the player are casting, and each spell has one or more types which defines many of its attributes, such as when it can be cast or what targets it can affect. Here are the most common card types in use in a standard game:

- Land: the basic building block of any deck, these permanents represent the mana available to cast spells. On each player’s turn they may play one Land from their hand onto the battlefield for free. Examples include Mountains, Plains, Islands, and Swamps

- Creature: summoning spells produce creatures, permanents which live on the battlefield and have the opportunity to attack other players. Nearly all decks have creatures, either for offense or defense. Examples include Goblins, Vampires, Samurai, and Cats

- Sorcery: these spells take effect immediately after casting, and then go into the graveyard. They can only be cast on your turn during the “main phase.” Examples include Fireballs, spells which kill multiple creatures, and spells that force people to discard cards from their hand

- Instant: like sorceries, these spells take effect immediately, but are unique in that they can be played on anyone’s turn. What’s more, they can be played in response to someone else casting a spell, and their effects resolve first. There is an entire section of this entry dedicated to such interactions (called the Stack). Examples include spells which counter other spells, draw cards, or tap creatures

- Enchantment: these permanents live on the battlefield and produce an ongoing effect or apply modifiers to other cards. They can be global in scope, limited to the player who cast them, or affect a single other card. Examples include spells which give a bonus to all creatures of a particular type, or grant a single creature the ability to fly

- Artifact: these permanents exist on the battlefield once cast, typically require any mana (not just that of a particular color) to play, and often have effects much like enchantments. Examples include artifacts which tap to create mana and equipment cards which can give a single creature additional power

- Planeswalker: in the lore of Magic, planeswalkers are powerful beings whose actions shape the destinies of empires, worlds, and whole realities. They are a special type of permanent that is distinct from others, with their own set of rules and abilities

- Token: tokens are special in that they aren’t cards themselves, but are a sort of “temporary permanent.” Often created by spells or creatures, when a Token leaves the Battlefield— whether it be to the Graveyard, to Exile, or even to a player’s hand—they simple cease to exist. Examples included nameless humans, basic zombies, or hordes of goblins

Tapping

Whether it’s to generate mana to cast spells or to commit creatures to attack, “tapping” a card—meaning to turn it sideways on the battlefield—is a very simple but important aspect of any Magic game. A card that is tapped can be thought of as busy or occupied; any effects which require it to tap can’t be used again until it has been straightened back out, typically at the start of one’s turn.

At its core, Magic is a game about resource allocation. If during your turn you cast a lot of spells, tapping all your lands for mana, you may have a lot of effects happening but you won’t have anything left to counter the opponent on their turn. If you assign all of your creatures to attack, which taps them, they won’t be available for defense if you yourself are attacked. Knowing when to cast what kind of spell—and when to hold back to respond to your opponent—is a key skill for all players.

Turn Order

After each player has shuffled their library and drawn seven cards to create their opening hand—which can be redrawn as a “mulligan” or do-over depending on the format being played—play begins. The player chosen or determined to go first will start their turn, and play will continue clockwise around the table, or alternating in a two-player game. As you move through the turn phases, it’s useful to call them out, to make sure everyone is clear on what is happening and what actions are available.

The following may look complex but every player follows the exact same format for every turn so it becomes second-nature in a very short period. In casual games, phases in which there’s nothing to do are often skipped completely, helping keep the action moving.

Beginning Phase

At the onset of one’s turn several things happen to set the stage for play.

- Untap Step: all permanents on the active player’s battlefield untap, meaning they are ready to be used again. This includes lands, creatures, artifacts, and any other card that was turned sideways

- Upkeep Step: some cards have effects which take place in this phase, such as paying a life to draw a card or requiring mana to continue an effect. Instant spells may be played during this phase, by any player

- Draw Step: after the untap and upkeep phases, the player whose turn it is draws the top card of their library and puts it into their hand

Main Phase 1 (pre-combat)

The main phase is special because this is the only time permanent cards can be played. This means that Lands, Creatures, Enchantments, Artifacts, and Planeswalkers can only be cast during this phase. Similarly, Sorcery spells can only be cast during a main phase.

Combat Phase

Combat is broken into multiple steps, mainly because the specific timing of some instant spells and other card abilities matter a great deal during this part of the turn. Some cards have effects which take place when attacks are declared, or when damage is dealt, and keeping them all straight is important for smooth gameplay.

- Beginning of Combat: this is an opportunity for any player to play Instant spells or activate abilities before the rest of combat

- Declare Attackers: in this step the active player decides which creatures are going to attack (if any), and what targets they are going after. In Magic creatures can only attack opposing players, Planeswalkers, or special cards called Battles, and each attacking creature may be assigned to attack a different target. Note that creatures that entered the battlefield this turn can’t attack—they have what’s called “summoning sickness.” All attacking creatures become tapped

- Declare Blockers: the player(s) being attacked may now assign blockers to defend against the attacking creatures. Multiple creatures can block a single attacker, but a single blocker cannot defend against multiple attackers. For example, two rats could defend against a single vampire, but a single goblin could not block two serpents. Assigning blockers is entirely optional, and only untapped creatures can be assigned for defense

- Combat Damage: this step is where all combat damage is applied to all relevant creatures. Damage is applied to all targets at the same time—meaning you can’t decide to resolve one set of attacker/blocker before another—though some special card abilities circumvent this practice. No matter how big an attacker is, barring special abilities, even the smallest blocker prevents its damage from reaching its target

- End of Combat Step: after all damage is applied, there is one last opportunity for Instants to be cast or card abilities to be used before combat finishes

Combat can get very complex very quickly, particularly in four-player game formats. While it may be tempting to rush through the steps, it’s important to complete each step in order—assign all attackers before anyone begins assigning blockers, and so forth. It is also worth mentioning that Instant spells and similar card abilities can be used at any stage of combat; for example one player may cast a Lightning Bolt at the beginning of combat to remove a creature before it can attack, or someone may cast a buffing spell after blockers are declared to ensure their creature doesn’t die.

Main Phase 2 (post-combat)

After combat there is a second Main Phase, with the same rules as the first: Permanents and Sorcery spells can be cast here.

Ending Phase

The last opportunity for players to interact on someone’s turn, this phase also resolves any end-of-turn effects.

- End Step: Many cards have effects which trigger on a player’s end step, and this is when they happen. Similarly, this is the final opportunity for any player to cast an Instant or activate a card ability before play moves to the next player

- Cleanup Step: if the active player has more than 7 cards in their hand, they must discard until they only have 7. Discarded cards go into the Graveyard

Once one player’s turn is done, the next player begins their turn and the process begins anew!

Winning the Game

In short, a player wins a game of Magic by being the last one standing.

Depending on the game format, each player begins with 20, 40, or some other amount of Life. A player who reaches 0 life has lost and is removed from the game; in a two-person format, that’s the end. In a game with more than two players, all of that player’s cards and ongoing effects are removed.

There are other conditions which allow players to win or lose the game, such as not having any cards in your library when you need to draw or accumulating enough poison damage. Meeting specific card requirements will also win (or lose) the game, but these conditions will be clearly explained on the card in question. In general however, most people win the game by their opponents all having been brought down to 0 life.

Creature Cards

Magic has no lack of different creatures players can bring to the battlefield. From humans to serpents, gods and spirits, nearly every deck is going to have at least one creature in it either to attack others or for defense. What’s more, many creatures have additional abilities which make them uniquely suited to further a goal, be it generate more mana, attack opponents before they can react, or create even more creatures.

All creatures, regardless of their color or type, have two stats which govern how they perform during combat: power and toughness. A creature with 1 power and 2 toughness would have it displayed like this: ![]() Always shown in the bottom-right of the card, the first number is a creature’s power, or damage dealt during combat, with the second being toughness, or its ability to withstand damage.

Always shown in the bottom-right of the card, the first number is a creature’s power, or damage dealt during combat, with the second being toughness, or its ability to withstand damage.

When attacking, a creature will deal damage equal to its power. If a creature is dealt damage equal to or exceeding its toughness over the course of a single turn, it dies and goes to the Graveyard. This means a 1/1 creature probably isn’t very threatening, both because it can’t do much damage and it can die very easily, whereas a 10/20 creature can do lots of damage and withstand a ton of punishment before going down.

Many creatures are more than just their power and toughness, however, and can possess a great number of special abilities. Some abilities are simple keywords, representing a standardized power or ability that has been included in Magic long enough that its mechanics are well-known, while others are more unique or complex, and which will have their full rules written on the card.

Here are several of the most common and frequently-encountered creature keywords:

- Haste: traditionally, creatures cannot attack or use abilities which require them to tap during the turn they’re summoned to the battlefield. Creatures with Haste can ignore this restriction, and are fully able to tap on their first turn. This is a common ability often found on low-power creatures

- Vigilance: creatures with Vigilance do not tap when declared as attackers, which means they can attack and still be available to defend on subsequent turns. This is a powerful ability often found among White creatures

- Trample: typically, blockers absorb all damage coming from an attacker, no matter how small they are or how large the damage is. Attackers with Trample allow any overflow damage—damage that’s more than the defender’s toughness—to reach their target, typically an opposing player or Planeswalker. This ability is often found on Red and Green creatures, and makes for very powerful attackers that often require multiple blockers to prevent damage from getting through

- Flying: creatures that fly cannot be blocked in combat except by other flying creatures, or those with the Reach ability. This is an example of an evasion keyword, which limits what creatures can defend against it, and of which there are many

- Deathtouch: sometimes, even a single bite is enough to bring down the mightiest of opponents. Any damage dealt by a creature with Deathtouch is enough to kill another creature, even if it doesn’t meet or exceed its toughness. In this way even a 1/1 Deathtouch rat can keep a 20/20 Leviathan from attacking, lest the Leviathan die from a single scratch

- Hexproof: an ability seen not just on Creature cards but some Enchantments and Artifacts as well, Hexproof means no spell or ability an opponent controls can target that card. It can still be affected by spells which do not target—such as something that affects “all creatures”—but this ability severely limits the ways in which an opponent can interact with the card, and is a fantastic protection for permanents which are key to a deck’s victory

While there are many different kinds of creature abilities—including triggered abilities which take effect when certain conditions are met and activated abilities which require some sort of cost and may be used any time an Instant spell could—the rules for most, save the above keywords, will be printed directly on the card so everyone is clear about the card’s effects in the game.

The Stack

Okay, time to dive into the most complex—and complicated—aspect of any Magic game: the stack. Whenever a player casts a spell or activates an ability, it goes onto the stack before resolving. This means other players have an opportunity to respond by casting their own (Instant) spells or activating abilities before the first spell completes. If nobody has a response to a spell or ability, it resolves and play continues. If there is a response however, the specifics of the stack come into play.

Following a “last in, first out” process, each response to a spell—or response to a response—is placed on top of the rest, meaning the very last response will be resolved first, then the next, then the next, all the way down to the original spell or ability. Another great article about the stack can be found on the official Magic website. Here we will look at several straightforward examples first, and then a more complex one.

Example 1: Countering a Spell

In a four-player game, the active player wishes to cast the creature spell Goblin Guide during their first Main Phase. They pay the mana required, and the spell goes onto the stack. The player to their left has first opportunity to respond, and declines. The next player decides they don’t want that spell to resolve, so in response they play the spell Counterspell, which would functionally cancel the goblin spell. They pay the required mana, and this spell goes onto the stack.

Now the fourth player has first opportunity to respond to the casting of Counterspell, and then the first player, and so on until the entire table has agreed that there are no further responses. Note that it is possible for a player to respond to their own spells, after everyone else has had opportunity.

Finally, all effects on the stack resolve. Counterspell targets Goblin Guide and effectively cancels it, resulting in the original caster having spent some mana with nothing to show for it.

Example 2: Sneaky Combat Tactics

In a two-player game, the active player has two large creatures ready to attack their opponent, who has no creatures alive to defend. They proudly declare they are moving to combat. “In response,” the opponent says, and casts Blinding Beam, which taps two target creatures. They pay the required mana, and the spell goes on the stack. With no responses, the two creatures are tapped prior to the “declare attackers” step, meaning they are ineligible to attack. This is one reason it is important to hold to the proper turn order, to avoid having to re-wind or stop play to figure out when certain things happened.

While players casting spells or activating abilities are most often what trigger reactions, certain turn steps also allow responses, such as the beginning of combat or the end step.

Complex Example: the Missy Elliott Special

In a two-player game—for simplicity, this example will get complicated enough—the active player is attaching Swiftfoot Boots onto a creature they control. This artifact gives a creature Haste and Hexproof, meaning no other player can target it. The required mana is paid, and the action of attaching the boots goes on the stack.

The opponent, not wishing to see the permanent become Hexproof, casts Lightning Bolt in response, targeting the creature. They pay the required mana, and this spell goes on the stack.

Preventing this sort of action was the goal of attaching the boots in the first place, so the active player looks for a solution. They have a Crimson Acolyte on the battlefield, which grants “protection from Red” with a single white mana. They tap a plains and announce that the Lightning Bolt fizzles since its target can’t be hurt by red sources.

“Oh but wait,” says the opponent. Activated abilities, like the Acolyte’s granting of protection, are activated abilities, which means the action goes on the stack, before the effect takes place. “In response…” and they cast Midnight Charm, which deals one damage, targeting the Acolyte before it can grant protection. The opposing player pays for the spell and this effect now goes on the stack.

Frustrated with the whole affair, the active player casts their own Lightning Bolt in response, targeting the opposing player. They pay their mana and this effect goes on top of the stack.

So what does the stack look like at this point?

- Player 1: Lightning Bolt (instant spell, targeting Player 2)

- Player 2: Midnight Charm (instant spell, targeting the Acolyte)

- Player 1: Crimson Acolyte: grant Protection from Red (activated ability, targeting the creature)

- Player 2: Lightning Bolt (instant spell, targeting the creature)

- Player 1: Attach Swiftfoot Boots (activated ability, targeting a creature)

Because the stack resolves top-down, first the Lightning Bolt resolves and the opponent takes 3 damage. Then Midnight Charm, targeting (and destroying) the Acolyte. Since the Crimson Acolyte doesn’t exist any more, it’s activated ability—to grant protection—can’t be used. The second Lightning Bolt resolves, killing the creature. Then finally, since the Swiftfoot Boots no longer have a valid target to attach to, they stay put.

So what was the end result of this back-and-forth? Two creatures died, a player took 3 damage, and a whole lot of mana was spent. Was this effect worth the mana and back-and-forth? The answer highly depends on the overall board state, the specifics of how each player’s decks were designed, and what cards were available in hand.

As one can imagine, Stack interactions in games with more than two players can get almost maddening to visualize. This is why the strict organization and priority process should be followed every time, to avoid the already complex process from getting unrecoverably convoluted.

Resources for New Players

My hat’s off to you if you’re still reading after that dive into the complexities of the Stack. It’s finally time to look at some great Magic: the Gathering resources for new players, aimed at helping you get into the game, learning its systems, and having fun!

A very popular format of Magic I enjoy is called “Commander,” where each deck is helmed by a unique creature or Planeswalker. This is a four-player format and many local gaming stores have nights dedicated to playing Commander, making it very easy to find live opponents to play with and against.

Additionally, there are many pre-constructed decks that contain everything you need to get started with the Commander format. Each “precon” contains 100 cards all focused around a theme—such as “ghost warriors” or “dragons” or “lots and lots of enchantments”—and the included cards are usually worth more than the purchase price of the set. If you decide that Magic really is for you, you may eventually start creating your own decks, but when starting out it’s hard to go wrong with picking out a precon you think you’ll like and trying it out.

Here’s a great review of the best precon Commander decks out now, ranked not only by relative play strength but also by value: The Best Commander Precons (TCG Player). All of the decks listed are available at Amazon or (much more preferably) by order from your local gaming store.

It often helps to see other people play a game before diving in yourself, and this is where the Command Zone YouTube channel really shines; not only does it host some very, very knowledgeable people, but it also makes the interactions between cards very clear and easy-to-follow. The production value is very high and while I’m not super big on the reality show-style format, I maintain that it’s a great place for people new to Magic to learn more about the game and how cards interact.

There is a free-to-play, official Magic: the Gathering video game called MTG Arena, available on almost a whole host of platforms, which does a good job introducing new players to the concepts explored in this article, as well as several different formats of Magic play, including Historic, Alchemy, Commander, and others. Well worth checking out!

In Conclusion

Magic: the Gathering is a game that can be both complex and complicated, particularly as interactions layer on top of one another. That said, it is a remarkably fun game that balances skill—both in deckbuilding and careful play—and random chance. It’s exciting to see how different decks work, what different cards exist, and how everything fits together, all in a social setting.

In another gaming-related post I mention how important it is to find a group who shares the same values as you do, and to a large degree this extends to Magic as well. Some people simply want to win at any cost, others want to have their deck do flashy things, and some are there just for the social aspect. It may take time to figure out what kind of player you are, and the kinds of players you want to play with, but having a solid understanding of the base rules will go a long way to making the experience fun, regardless of where you sit down.

Thank you so much for coming along with me on this dive into the basics of Magic: the Gathering. Do you have more questions or suggestions for other entry topics? Use the link in the sidebar to send me an email.

Happy playing!

Header image taken from stolendroids.com