For most, an internet “content filter” is something you install to keep your children away from unwanted websites, or something put in place at work to ensure employees don’t access social media. However with the evolution of web technologies and the proliferation of trackers installed both in websites and “smart” devices, it is imperative that everyone—and I do mean everyone—take steps to block unwanted traffic on their network.

I discussed ad-blockers, software which lives on a computer and helps hide annoying and potentially-harmful ads on webpages, in my presentation about cybersecurity to a group of financial and investment professionals some years ago. In that time the need for ad-blockers has only grown; sites from Google to eBay and Facebook have been caught selling ad space to malicious actors who then sent viruses to end users who didn’t have to do anything more than visit a website; even viewing the ad was enough to expose their computers to takeover, ransom, or outright deletion.

Both Mozilla Firefox and Google Chrome have reputable and effective adblockers available, and I highly encourage all my readers to have one installed on their system. Even iOS and Android phones can get adblockers from their respective app stores. Not only does blocking ads reduce webpage load times and make most video-viewing experiences much improved, it also helps prevent large data-harvesting companies from compiling information about you as a user and selling that profile to others.

In brief, install an ad-blocker.

Unfortunately, ad-blockers can’t catch everything, and there aren’t blockers available for many devices, such as smart TVs, internet-connected thermostats, and the like. This is where a network-wide content filter comes into play, blocking traffic to known-bad or known-suspicious online sites, regardless of what device makes the request.

Why should I care if my TV phones home?

Just as many (if not most) websites compile information about the people who visit them, as more and more devices come online to create the “Internet of Things” (IoT), marketers and companies realized there was big money to be made in the collection and selling of this new treasure trove of data.

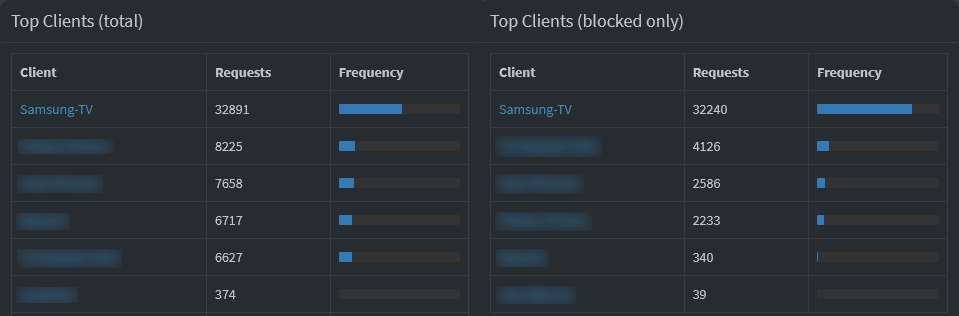

Here is a snapshot taken from my own network content filter, where traffic over a single 24-hour period was broken down by devices making the most requests (unique websites), and those for whom requests were blocked. Out of 32,891 requests made by my television, more than 32,000 of them were stopped before they reached the internet. This means that more than 98% of my TV’s internet traffic was ad-related.

To put this in perspective, the TV was on for only six hours that day, while the next several entries on both lists represent computers and phones which were in use almost constantly throughout the morning, afternoon, and evening. The sheer volume of traffic my TV generated is staggering, and I see this pattern every time I switch it on—I can immediately see the spike in network requests, regardless of how it’s being used. Tallying the top 6 devices in both categories, this means more than 66% of the requests made on my network were ad-related. That’s insane.

Why was my TV trying to “phone home” so much? Because the data it collects—about when it’s turned on, what is being watched, whether I’m using Netflix or YouTube, what the volume level is, and so much more—is worth real money to Samsung and its partners. I don’t have a cable subscription or watch any over-the-air programming, meaning largely the TV is just a convenient gateway to the various streaming services I enjoy, and it wants to report as much as possible back to headquarters, to help build a profile about consumers in general and me in specific.

As many people install and utilize “smart” devices, they often fail to realize just how much information they are giving away, and how giving away that information in no way helps them as a consumer.

But I have nothing to hide

The “nothing to hide” argument has been soundly debunked and countered time and time again. We all possess information we don’t want others to have, or don’t feel that they have the right to look at. I wrote about this topic more specifically in my article Freedom and Anonymous Data, and if anything my sentiments are even more true today than they were in 2019. Information is power, and there is a great disparity between the end users (us) and the large brokers who harvest and sell details of our online lives.

Taking control of your network traffic through the use of ad-blockers and content filters goes over and beyond just protecting your personal computer from harm and saving your internet bandwidth; it can also mean that the devices in your home can’t spy on you nearly as much.

When I say “you need a content filter,” I don’t just mean academically. You, the person reading this, needs one.

If you’d like to know more or have questions on how to help protect yourself online, please reach out and email me. I want to help as many people as possible secure their networks and have a better computing experience.

Header image by Pete Linforth from Pixabay