Content Warning: This story includes references to the horrors of the Holocaust, several generations removed. It also includes descriptions of medical gore and of self-harm which may not be suitable for all audiences.

Weeks after the funeral, Erik summoned up the courage to start sorting through his mother’s house. The air was still—eerily so—and though he walked through the halls and rooms of his youth, nothing seemed familiar, as if all of the pictures, furniture, and trinkets had been replaced with immaculate copies, suspiciously lacking the life and memories that had been built up around them.

Opting to work on the hardest room first, he walked up the stairs, heavy footfalls on tired carpet. Opening his mother’s bedroom door, he tried unsuccessfully to keep from crying anew. All of her dresses hung neatly in the closet, unworn since the diagnosis two years prior. With a sigh Erik began pulling boxes from the upper shelves, gingerly handling the many breakables she collected.

A small cardboard package had “Grandfather” written in his mother’s beautiful, flowing handwriting. His family had never been very open about their history, and he knew almost nothing about his mother’s side. Taking a seat on the floor, he carefully slid a finger beneath the aged masking tape, unsealing the long-untouched box.

The small canvas pouch inside had faded text stamped on it, next to the infamous eagle iconography of the Third Reich. He wrinkled his nose in disgust—no wonder the family was quiet about its roots prior to immigrating to America. Erik didn’t speak German, but the internet provided a serviceable translation: Whermacht Suicide Kit

His brow furrowed. Did his great-grandfather commit suicide? Was this a standard part of a soldier’s kit? A macabre suspicion raised, he unclasped the pouch. Inside he found a small roll of what appeared to be mints, a single razor blade, and a tiny flip-book that seemed to include instructions. With phone in hand, Erik began translating the curious little pamphlet.

Suicide is not a noble death, and will shame your memory and your family for generations. You weaken the Fatherland by your own hand. If you are still committed to this shameful act, please obey the instructions contained herein, that we may better understand these impulses and keep this tragedy from befalling other soldiers.

Mouthing his confusion, he suddenly looked about the room as if to verify he wasn’t being watched—the situation was far beyond anything he expected to encounter while going through his late mother’s belongings. Not knowing what he would encounter next, he turned the small page, at once horrified and fascinated.

Before ingesting the included Zyclon C tablets, make an incision lengthwise across your brow, through the bone of the skull. Take care not to damage the sensitive brain tissue underneath. Continue the incision up and over the crown of your head, and remove the front quarter of your skull. See next page for examples.

Erik couldn’t keep his fingers from flipping the thin paper. On the next page was a disturbingly helpful diagram of a placid human face, in both profile and straight-on, showing a dotted line extending from temple to temple, both around the front of the forehead and up over the hairline. His stomach twisted of its own accord. With trembling fingers he continued reading.

Once you have exposed the frontal lobe of your brain, take a photograph of the exposed tissue. If you are unable to do so, ask a fellow soldier for assistance. They, having been unable to sway you from this course of action, will at least recognize that they will be helping the cause of medicine and saving future lives. The photograph will be used by our determined scientists to determine what physical changes the brain undergoes when a decision to commit suicide is reached. Give this photograph to a trusted ally, who will deliver it to Command.

In suicide you are depriving Germany of a powerful soldier. If you fail to ensure this photograph returns to Berlin, you are depriving Germany of future advancement—your death will have been truly selfish.

He retched.

Upon regaining his composure, he flipped the page, only to drop the booklet and run to the bathroom to empty his stomach, the blow of nausea striking him like a runaway train. Not content to merely provide textual descriptions of the procedure, the next page contained example photographs, a full spread of dull-eyed men with their brains exposed, blood wiped away for the camera.

It took Erik long minutes to regain his composure, his stomach having heaved well past the point of being empty. Every limb shook as he braced himself against the white porcelain, slowly rising to his full height. He would never—could never—understand why his mother kept such a foul reminder of the horrors of the twentieth century, but he was determined that he himself would not let the story continue.

Angrily throwing the roll of murderous poison pills and razor back into the bag, he finally forced himself to touch the foul booklet, refusing to look until he closed it, shutting away the terrible images and instructions. With a disgusted sneer he was about to add the pamphlet to the bag when something on the back cover caught his attention.

Slowly uncurling his fingers, he looked closer, praying that his eyes had deceived him. Dr. Dieter Schreiber, the inscription read, Head of Research at Berlin Medical Association.

His great-grandfather wrote the instructions himself and had ordered their distribution to Nazi soldiers.

The thin paper fell from numb fingers as Erik stood, unable to comprehend his family’s role in the terrors of the second World War.

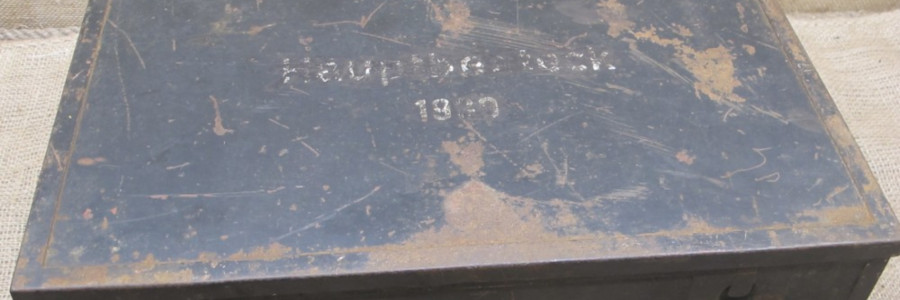

Header image of a 1939 German “Hauptbesteck” surgical tool set box.

Story seed from a very, very bizarre dream I had recently. Maybe writing this is my way of dealing with the revulsion I felt upon waking.