My eyes exploded with a blinding light, bright enough to leave afterimages even as I tried to find relief behind my hands. Tears streamed down my face and my head throbbed with a rhythmic pounding that threatened my very eardrums. I writhed on the floor, unable to control myself, unable to make sense of my surroundings beneath the onslaught of light and pressure. Eventually, slowly, I was able to catch my breath, ragged gasps bringing sweet oxygen into my lungs. The intense pain subsided, and my eyes gradually began to adjust. I could feel cold tile beneath my hands and face, and started to discern shapes in the bright chamber. Where was I, and what had happened to me?

Though it turned my stomach in knots, I finally forced myself to stand and take stock of my surroundings. Four off-white walls stood bare, unadorned, lit by the harsh overhead lamps which seemed bright enough to electrify the very air I breathed, stale and arid. The room was small, pantry-sized, but contained very little. A thick metal door sat ajar just before me, while behind me some manner of pressure chamber stood open, large enough for a single adult, with all manner of tubes and piping connecting it to the floor and ceiling. A small monitor sat next to the unit, the green text on black background blinking in emotionless, repeated announcement.

STATUS: ERROR_

Sitting down and leaning against one of the walls, my senses already overwhelmed, I tried to peer through the fog that was my mind, to make some sense of everything. I knew there had been a bright flash, but that it had seemed far away, filling the sky. Lots of running, so many people running, and soldiers letting some of us inside. Then the big door closed, and I was crying — a lot of us were crying — and I somehow fell asleep, only to wake up on the floor of that room.

My shoes were nowhere to be seen, but my simple shirtwaist dress seemed to have survived without incident. I had been making dinner when the phone rang, pulling me away from my new glass cookware, and just after I answered the sky outside the kitchen window seemed to explode. The specifics were still hazy, uncertain, but I knew they would come back to me in time. John always said I had a good memory, that I never forgot anything. I froze anew, eyes awash with fresh tears, vision blurring as my body was wracked with uncontrollable sobbing.

John. My husband John.

John who was picking up our son from school.

John who didn’t make it into the bunker.

Eventually wiping the tears from my eyes, I steadied myself; I didn’t know what the outside world was like, whether or not my family had survived. With a deep breath I rose and approached the door, noticing the eerie silence that seemed to fill the bunker, none of the normal sounds of habitation I expected.

Lights flickered in the long hallway outside my room, casting moving shadows from discarded medical equipment. Large cannisters of oxygen, turned-over gurneys, and the occasional IV pole were strewn about the otherwise empty passage. Doors to other rooms like mine stood firmly closed and locked, per the small electronic read-outs near to each. With uneasy footsteps I started to make my way through the corridor, it looking to all the world like a horror hospital from one of the late-night movies I refused to watch.

The cold tile beneath my feet gave way to ragged carpet, obviously well-worn with age, as I approached the administrative halls. I remember having been that way once before, after John brought home three tickets to the vault — some prize he had won at work. The scientists took our measurements and various readings, typing them into bulky computers, assuring us that all was normal. “We hope you’ll never need those tickets,” they said, “but we’ll be ready in case you do.”

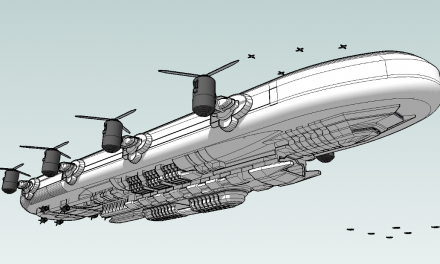

Everything once had seemed so pristine, so new, but the dingy and dirty carpet, cobwebs, and toppled bookshelves told a very different story. Hunting through a desk I found several unopened tubes of nutri-paste, and I was thankful my dress had pockets — not the most popular fashion, but certainly functional. The air still tasted stale, like the recyclers and scrubbers had been operating for a long time, even as I moved into different areas of the bunker. The bunker, that’s right. The Vault was a self-contained habitat built into the side of a mountain, in case war ever came to our shores. Similar vaults were being built all across the country, but California had some of the first.

The sound of skittering in the darkness snapped me from my memories. Something else was alive in here with me, and it didn’t sound human — more like chitin against metal. Grabbing a small statuette from a nearby desk, I armed myself the best I could. I was sure the winner of “Vault World’s 1954 Innovation Expo Judges Award” wouldn’t mind my taking it. The skittering drew nearer, perhaps lured by my shallow breaths as I gripped the smiling statue tightly like a small cudgel. It sounded large, like the way a big dog’s claws might scrape across a floor, but I was sure it wasn’t a dog.

With a fluttering hiss the thing jumped out of the corridor and into the small office space with me, the largest cockroach I had ever seen. Yelping in surprise more than screaming in anger, I brought the statuette down with all of my might. Whatever it was expecting, it surely hadn’t anticipated running across a barefoot housewife armed with a company award. I felt the thing’s hard shell crack under my onslaught.

With vile bug viscera dripping from my hands, I dropped the ruined improvised weapon. Growing up in Northern California, most of the insects I had dealt with were small ant colonies, pesky wasps, and the occasional potato bug, and none compared to the girth of that dead cockroach. Its body was bigger than a football, with spindly legs and antennae that twitched as life left its multi-faceted eyes.

Skirting around the mess, I quickly made my way out of the administration wing, making sure to step lightly near the large air vents inside of which more massive cockroaches undoubtedly lurked.

The underground complex was separated from the world by a large airlock, the exterior of which was designed to seal with a large, mechanical door not unlike a bank vault designed to hold fast against a nuclear apocalypse. I didn’t remember the huge, multi-ton door closing behind us during the blast, but I remember marveling at its construction during our tour of the facility. It was massive, wider than our car was long, and easily four feet thick. I remembered scoffing at the need for such a shield — war was ever-present on our minds but not in a “it will actually happen” kind of way — but I owed my life to the engineers who designed it and rolled it in place.

The internal glass doors leading to the airlock were covered in a thick orange soot, making it impossible to see what lay beyond, or even if the airlock was safe. A small alcove nearby held starched labcoats, safety goggles, and face masks, all covered in a fine layer of dust. Wiping a set clean and hoping it would provide adequate protection against whatever waited outside, I sought the access control panel.

If there’s one thing I knew, it was that scientists liked over-engineering things. My home blender had no less than seven different toggle switches, suitable for any conceivable combination of chopping and mixing in the kitchen. The control board nearest the airlock was more complicated than my blender by orders of magnitude. Switches and sliders and dials — none of them adequately labeled for a lay person like myself — covered most of the wall. Most of the indicator lights were off, save for a dim pulsing that showed the reactors were still mostly operational. I had passed through plenty of dark corridors and unlit passages in my exploration, but luckily it seemed like most of the systems were operational to some degree.

I looked for a large, distinct button like in the shows, the ones where heroes are able to save the day in the nick of time, but I wasn’t as lucky as those masked protagonists. I saw controls and meters that looked like they adjusted ventilation, water pressure, even the air conditioning, but nothing that jumped out as responsible for managing the doors. Many of the switches were labeled with serial numbers or other indecipherable engineer reference which meant nothing to me — I could run a PTA meeting, not repair robo-vacuums. One gage clearly showed the “external radiation level” and while I wasn’t a nuclear scientist by any stretch, the low level it reported seemed promising.

Not willing to take a chance at pulling, twisting, or sliding any of the available options, I took the direct route — after several minutes of weighing my options — and used a rusted rolling chair as a simple battering ram. The glass door spiderwebbed where I hit it, more easily than I expected. A second attempt sent glass flying into the airlock that had sealed out the world. Instantly a cold breeze brushed my masked face and sent shivers down my arms. Discarded papers — reports and the like from the scientists who were supposed to manage the vault — fluttered from the desk as the pressure equalized.

The enormous vault door sat ajar, knocked askew from its heavy tracts. The light outside was blinding, forcing me to raise my hand against the glare. With no concept of what I would find, I began walking. The outdoors had to be better than the near-silent crypt in which I had woken up.

These are the opening words of my second novel, A Home on the Wasteland. I have already posted several short stories and excerpts (heck, 30 of them) on this blog, long before I had the idea of compiling them all into one volume. Though work stalled on this project as I raced to complete my first novella, Pandora’s Box: A Weak Point between Here and There, it very much remains at the forefront of my writing mind and I want to dive back into the post-apocalyptic North Bay as soon as possible.

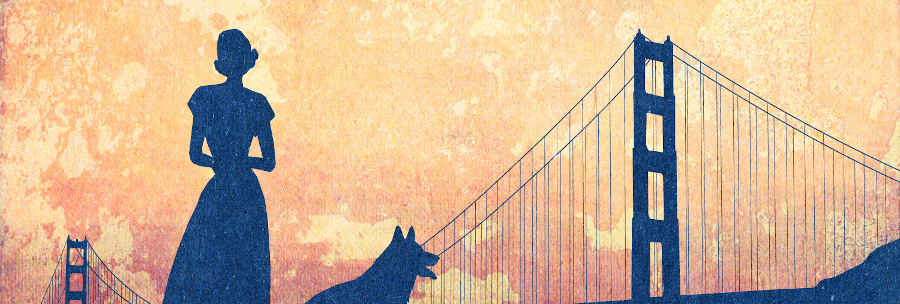

The header image for this post was taken from the phenomenal book cover put together by Joseph Irizarry, whose work speaks for itself. Click the following image to see the cover in its full glory—all ready for printing, when I finish up the novel. If you are interested in artistic commissions please by all means reach out to him with your ideas. He absolutely captured the feeling I wanted to convey with this novel and while it’s still a ways off, I can’t wait to see his work introducing my words to new readers on bookstore shelves.