Some items have intrinsic value—there’s no denying that food, water, and shelter are important staples for the human condition, and when they become scarce, fighting over those resources becomes understandably intense. There are plenty of other objects or ideas that don’t necessarily have value by their very nature, but are important socially, and are similarly fought over—the notion of freedom, a nugget of gold, a rare baseball card. I like to think that we all have those things that are important to us, that we see as core to who we are and what we do. Sometimes though the things people fight for makes me scratch my head.

Take long-standing myths like the Fountain of Youth or the Holy Grail. Individuals, armies, even whole countries have spent centuries and spilled countless blood trying to find objects or places that nobody has even verified exist in the first place. For some it’s an obsession; they’re convinced that they have some special ability or information that was denied to all those who came before. For others their concept or idea is the anchor to which they have leashed all of their hopes—if they only had whatever item, everything in their lives would be better and their problems would be behind them.

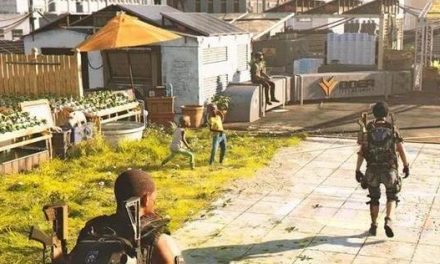

Those may be extreme examples, but I see the same thing every day—people fighting for something they think is important, whether or not it has objective value. Take this morning for instance. Israel and I were supposed to rescue some VIP from where he had been holed up in a safe room on the second floor of a mall. The place had been heavily barricaded by gassers who really wanted that VIP also. They had snipers outside, grunts on the ground, and plenty of angry, drugged-up fighters inside, plus the more technical among them trying to break through the keypad. All in all, not a fun force to go up against, but word from command was that this guy was integral to us taking back the city. The gang that had trapped him in there were convinced that he had some value to them as well, and they were trying everything in their power to break him out of the secure room—threats, explosives, lockpicks, everything. Not content to just wait him out—how much water could a safe room have—they set trying to cut him out. For drug-fueled gang-bangers, a lot of the groups around Washington had shown a great deal of organization.

Anyway, ours was to get the VIP out safely through whatever means possible, preferably before the gang made it through the door. The guards outside weren’t too bad—I know the trope is “laser sights on guns equal better aim” but putting them on sniper rifles is just a joke and seeing a bright-green line pointing right back to their position makes our job pretty easy. Whoever told this gang about the guy inside must have really upsold them on the idea that he had value—in the front mezzanine they had erected an honest-to-god light machine gun, the kind you see in those Vietnam war documentaries or mounted to armoured vehicles and the like. Apparently they had been expecting some external resistance and made sure they were equipped to handle it.

After rolling our eyes and cursing our commanding officers a bit for sending us into the lion’s den, Israel and I started to devise a plan. Normally long-range takedowns were his thing, but with the crowded hallways and twisting corridors inside the mall, there wouldn’t be much use for sniping. We both hefted shotguns we picked up from the guards outside, his a nice semi-auto and mine a two-barreled farm gun that would pack quite a punch, and we set about trying to flank the crew manning the big gun. Whichever one of us had a good shot first would take it, which would draw a lot of attention, giving the other opportunity to hit them from behind.

It took some doing, and more than a single grenade throw, but we finally convinced the gang that manning the turret was bad for their long-term health. The sandbags that protected it had been blown to dust so the gun didn’t provide any benefit to us after the fact, but it felt good to take away one of their big toys. We both made the note to tell HQ that these gangers had been exceptionally well-armed. That and there was going to be a nice collection of firearms and ammo in the mall for local resistance fighters once we were done.

We made our way up the stairs, past burned-out and looted shops, through frenzied gassers, and finally up to the safe room. I don’t know where they had picked up cutting torches, but pressurized bottles of oxy-acetaline do not react well to bullets. I’m glad that safe room was as secure as it ended up being; it would have been pretty embarrassing otherwise if we accidentally blew up our target. Nevertheless, the gangers were cleared out and we were clear to rescue the trapped VIP.

“Who?” the man asked nervously, finally unsealing the battered and beaten door after verifying our credentials. “I don’t know who that is—I’m an engineer who just barely slipped in here when the gangs took over.”

The guy the gang spent untold resources, and at least a dozen lives, trying to get to wasn’t in fact the person we thought he was. The guy we waded through rivers of bullets and took glancing shots to the vest to get wasn’t in fact anyone of import. Don’t get me wrong, saving a life is a great feeling, but we were both disappointed—to say the least—to find that the object of our search didn’t have as much intrinsic value as we had been lead to believe.

Isn’t that always how it is though? There’s some old saw that “the price of getting what you want is no longer wanting it” or somesuch, meaning we’re always looking for the next thing, never content with just having what we’ve earned. Even if we had managed to rescue the real VIP I suppose tomorrow we’d be off onto the next goal, the next search, the momentary success of the previous day fleeting and ephemeral in the face of the new.

Whatever ideological pontifications we made, the civilian ran off, promising to “stay in touch.” I have to admit, that made us laugh, a much-needed moment of levity in the wake of (ultimately) pointless slaughter.

Everyone had congregated on that mall under the false belief that the captive therein would be some sort of solution to our problems. What a thing it is, assigning value to something we’ve never ourselves verified.