It’s a common misconception that our higher-ups establish policies, make decisions, and operate with little to no government oversight. In reality the bulk of them are analysts, crunching the kinds of data that field operatives like Gaz and I gather, passing it up the chain with recommendations. “Action Y has a Z% of yielding X result” kind of paperwork. Sometimes they send us specific requests, like the names of each resident on a particular street, or scramble to answer questions we have, but in the end the day-in and day-out business of the agency is make recommendations, not final calls – that authority rests in the West Wing.

When word came down that the rules of engagement had been “relaxed,” it meant that someone, likely several someones, impressed upon the powers that be that El Seño needed to be brought in as quickly as possible, no matter the methods. It’s not common for the administration – any administration – to blanket-authorize actions which could later be construed as international war crimes, but luckily neither Gaz nor I thought we’d have to do anything truly heinous to get the job done.

I should clarify what I mean when I say “truly heinous.” Yes, I fully understand that most of the work we’re involved in would be unpleasant – at best – for the public at large to read about in the evening post. I won’t say this is a Bay of Pigs situation, there’s been a lot of learning since then, but extraterritorial killings, torture, and making deals with the proverbial devil aren’t in the “welcome to your new job” pamphlet. All of these things are regular, commonplace, frequent, and other synonyms for “business as usual.” Nobody at the higher end has to authorize any of that stuff; it flies so far under the radar it may as well not exist. When I say “truly heinous” I mean actions that would turn the stomach and land Gaz and I in front of several Hague tribunals. You’ll forgive me for not going into detail, but I’m pretty sure you have enough of an imagination to get creative – if we had to, we would.

As we rucked it back to the nearest rebel base – maybe seven klicks from the estate where El Seño thought to murder us – we had plenty of time to review our options. We had done a fair amount of damage to the big man’s reputation and relationship with the people by exposing his head priest and the child exploitation ring they ran, and soured the cartel’s cozy connection with the military by instigating some not-so-friendly fire incidents, but we knew that any truly extreme measure may cause his massive PR machine to turn it all back around on us, the “meddling Americans,” and painting himself as the hero or savior of Bolivia.

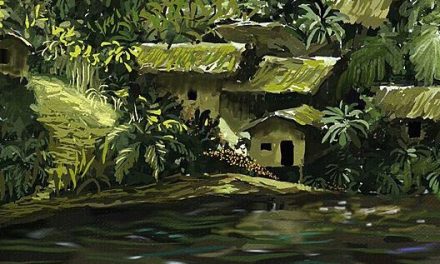

Exhausted, almost out of ammo, and covered in a delicate mix of sweat and jungle mud, we made it back to base as the sun was illuminating the tops of the Andes. The four-wheeler we stashed for the mansion raid would have been a faster, and arguably more comfortable, trip back, but we couldn’t risk making that much noise with half of the cartel hunting through the jungle for us. We called in our situation – grumpy but unhurt – and stole some rack time.

That we escaped his trap was a huge amount of huevo on El Seño’s face, and one that may shake his followers’ faith in their larger-than-life leader. It was time to use that to our advantage and bring our extended South American trip to a successful close.