Growing up with parents who both worked in the medical field, I was often regaled with stories of the extraordinary or weird situations patients presented either in the hospital or when calling 911. A pair of anecdotes from my mother have long stuck in my head, and I think they have gone a long way to inform how I regard injury and discomfort in myself.

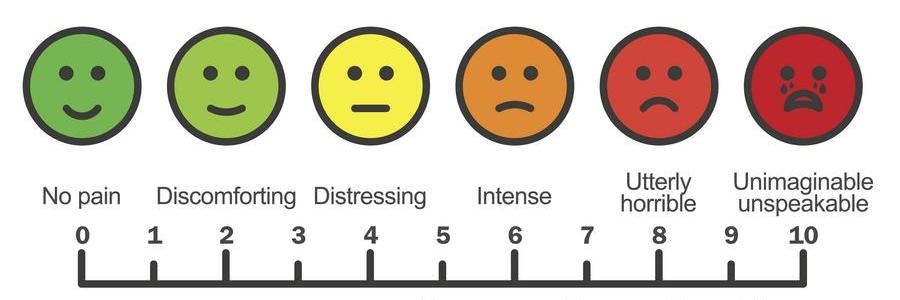

In the 1990s hospitals across California began tracking how patients were feeling compared to when they entered medical care. These questions were especially useful when gauging the effectiveness of drugs like morphine or other opiates. Less looking for a marker against an objective scale, they were tracking whether a patient’s pain was better or worse over time, relative to earlier answers.

My mother told me of a patient who was perfectly lucid, awake and aware of her surroundings, who had entered the hospital for a minor injury. When asked about her pain, on a one-to-ten scale, she calmly replied “oh, this is probably a ten,” with a nonchalance that didn’t quite validate her answer.

She also mentioned, perhaps at the same time, a male patient who had suffered a grievous wound, who was suffering from blood loss and was obvious in terrible distress. “Three or so” was his answer, the words spat from behind teeth clenched from pain.

Though I know I’m conflating this conversation with a scene from the TV show ER, I clearly remember the image of a man wheeled into the hospital after a mishap with a snow blower (it hasn’t measurably snowed in my hometown since 1870), and the doctor asking “did you lose any fingers?” The man’s buddy held up a plastic baggie filled with ice and blood and said “nope, got them all here!”

Friends and family know that I dislike taking medication, particularly for pain management. Perhaps it’s a hold-over from my grandfather’s stoicism or framing my own discomfort in reference to the medical stories shared around the dinner table, but my wife knows I’m feeling some true discomfort if I ask for a bottle of acetaminophen or decongestant; usually I prefer to just “tough out” an illness.

I’m lucky that I haven’t had much experience with hospital inpatient services in my life, but of course I suffer the aches and pains associated with no longer being twenty years old. Some months ago I threw my back out reaching for something in the backseat of my car—talk about embarrassing. After several days of hardly being able to get out of bed, I finally scheduled an appointment with my doctor. She asked “on a scale of one to ten, how much pain are you feeling?”

It was the first time I could remember where I actually thought about my subjective pain scale, and what it meant to be injured. Often the flippant one, I probably responded with “I’m still capable of conscious thought, so it’s not a 10” or something similar, with a forced grin.

For myself, I largely can’t conceive of pain that would rate higher than perhaps a six, because any injury or harm that I would subjectively put in the upper half of the scale would likely leave me a blubbering mess. Heck, my go-to when I describe level nine is “I would be too busy screaming to respond to questions,” and ten is “I would have passed out from screaming so much.”

It’s fascinating to me how the human body can adapt to different stimuli, and even become accustomed to it. I have a friend who was an avid backpacker before being struck with a debilitating autoimmune disease that made even walking from her car to the front door of her office a laborious and painful chore. Over time she began to describe her condition as “the usual,” even though she was in a constant state of lingering pain that, if introduced suddenly, would likely leave anyone else writhing on the floor. There’s a lot to be said for analogues between physical and mental/emotional pain here as well, but I’ll leave those alone for now.

After several years of exhausting treatments, my friend has bested the disease and is well on the road to recovery, starting to return to the summits and peaks that make her happy. Though I imagine she still feels some measure of pain, the sheer reduction in its severity has made all the difference in the world to her, giving her her life back.

Thinking about her story leads me to consider the normal and usual aches that perhaps I myself have grown accustomed to, and I find it difficult to imagine what life would be like without them, because they have become just part of the background fabric of my life. I functionally don’t notice their effect on me because they’re constant companions, lost in the noise of the day-to-day.

Sometimes though things fall back into place, either through accident or design, and for some time I can remember because some feeling will ebb or disappear completely. it makes me sit back and wonder at how my daily experience would change if I didn’t have them.